Dostoevsky, Crime and Punishment, Part Four, Chapter 4 commentary - completed and updated

100 Days of Dostoevsky's Notes from Underground and Crime and Punishment September 1 - December 10, 2024

100 Days of Dostoevsky's Notes from Underground and Crime and Punishment

September 1 - December 10, 2024

November 7 - completed on November 8

Crime and Punishment Part Four, Chapter 4, 18 pages

Next passage:

November 9 - to be posted on November 10

Crime and Punishment Part Four, Chapter 5, 20 pages

How does one travel the route from transgression to salvation? Humility, repentance, acceptance, love, forgiveness, redemption, transcendence…

In short - it takes a miracle…

All the final novels of Dostoevsky - the Great Five - are books of miracles of Biblical proportions. Crime and Punishment bears witness to the resurrection of the human soul and serves as a reinterpretation of the narrative of the raising of Lazarus; The Idiot - the reenactment of the Book of Revelation; Demons - exorcism of the Gerasene demoniac; The Adolescent - the expulsion of the money changers from the Temple; Brothers Karamazov - the wedding at Cana, the first miracle of Christ.

Dostoevsky may be known as a deeply psychological writer, but it is the theological and spiritual aspects of his late work that make him a prophetic figure in world of literature on the scale of Virgil, Dante, Milton, and Goethe.

Mitya Karamazov, the most perfectly flawed character of Dostoevsky, a great homage to both Goethe and Schiller, makes the following observation in Brothers Karamazov:

“I can't bear it that some man, even with a lofty heart and the highest mind, should start from the ideal of the Madonna and end with the ideal of Sodom. It's even more fearful when someone who already has the ideal of Sodom in his soul does not deny the ideal of the Madonna either, and his hear burns with it, verily, verily burns, as in his young, blameless years. No, man is broad, even too broad, I would narrow him down. Devil knows even what to make of him, that's the thing! What's shame for the mind is beauty all over for the heart. Can there be beauty in Sodom? Believe me, for the vast majority of people, that's just where beauty lies--did you know that secret? The terrible thing is that beauty is not only fearful but also mysterious. Here the devil is struggling with God, and the battlefield is the human heart.”

A human being is WAY too broad - but how to narrow us down? This broadness extends to both our ability to do good - AND our ability to do evil… When we fail - and fail catastrophically - should we be ostracized and discarded? But who will do the casting out? The one without sin? Show me that human being…

Let the battle for the human soul commence…

These are but a few immediate things to ponder…

***

Comment continued…

Sonya, Sophia, whose name means wisdom - root of the word philosophy - love of wisdom… In Russian the word for philosophy - философия - actually contains the name София.

Sonya is also the love and forgiveness that are essential for the possibility of redemption post transgression… I always tell my students to watch out for the moment in War and Peace when a character states “I understand nothing” - this moment of self realization allows a character to become self-aware and humble - a precondition for wisdom and transcendence. Raskolnikov is a man of ideas which evolved to the point of his murderous severing of himself away from humanity - the proverbial man born of ideas that terrified Dostoevsky on the last page of Notes from Underground. Sonya interjects on behalf of Raskolnikov’s humanity when she exclaims:

“You know nothing, nothing... ah!"

“Sonya spoke as if in despair, worrying and suffering and wringing her hands. Her pale cheeks became flushed again; her eyes had a tormented look. One could see that terribly much had been touched in her, that she wanted terribly to express something, to speak out, to intercede. Some sort of insatiable compassion, if one may put it so, showed suddenly in all the features of her face.”

If anything can save Raskolnikov from himself and his anti-human rationalizations - it is Sonya’s “insatiable compassion.”

Sonya feels the spiritual pain of the world deeply and personally - she understands the despair of her step mother who is at war with the world because of her faith in justice:

"Beat me? How can you! Beat me-Lord! And even if she did beat me, what of it! Well, what of it! You know nothing, nothing... She's so unhappy; ah, how unhappy she is! And sick... She wants justice... She's pure. She believes so much that there should be justice in everything, and she demands it.”

Sonya feels guilty not because of her sinful life - but because when her father asked her to read to him - she brushed him aside and stated she must run - and because she was unkind to her step mother when she asked for the lace collar which she would not be able to wear since she had no proper dress… Thus Sonya’s self penance - her reaching out to Raskolnikov…

Sonya bears the burden of her own humanity by extending her love to all who cross her path. She was friends with Lizaveta, the innocent victim of Raskolnikov’s rationalizing of his greatness through transgression. They used to read from the Holy Book together, they used to talk of faith…

“"But maybe there isn't any God," Raskolnikov replied, even almost gloatingly, and he looked at her and laughed.

Sonya's face suddenly changed terribly: spasms ran over it. She looked at him with inexpressible reproach, was about to say some-thing, but could not utter a word and simply began sobbing all at once very bitterly, covering her face with her hands.

"You say Katerina Ivanovna is losing her mind, but you're losing your mind yourself," he said, after a pause.

About five minutes passed. He kept pacing up and down, silently and without glancing at her. Finally he went up to her; his eyes were flashing. He took her by the shoulders with both hands and looked straight into her weeping face. His eyes were dry, inflamed, sharp, his lips were twitching ... With a sudden, quick movement he bent all the way down, leaned towards the floor, and kissed her foot. Sonya recoiled from him in horror, as from a madman. And, indeed, he looked quite mad.

"What is it, what are you doing? Before me!" she murmured, turning pale, and her heart was suddenly wrung very painfully.

He rose at once.

"I was not bowing to you, I was bowing to all human suffering.””

And here we reach the point Dostoevsky will eventually call “надрыв” in Brothers Karamazov - which is translated as breaking or strain or laceration - a point where the soul comes to the moment of truth - and will be lost to darkness or ascend to light along a road of painful physical suffering and profound spiritual introspection.

Raskolnikov needs Sonya because she too destroyed her purity, the sanctity of her body - he needs to understand how she can stand life and face people after her great sin… She sacrificed herself for other - he for his own rationalization of his own self-assertion as a man above men. Why is she still so pure despite the sin? Why doesn’t she just kill herself and end the suffering?

“"Ah, how could you say that to them! And she was there?" Sonya cried fearfully. "To sit with me! An honor! But I'm ... dishonorable... I'm a great, great sinner! Ah, how could you say that!"

"I said it of you not for your dishonor and sin, but for your great suffering. But that you are a great sinner is true," he added, almost ecstatically, "and most of all you are a sinner because you destroyed yourself and betrayed yourself in vain. Isn't that a horror! Isn't it a horror that you live in this filth which you hate so much, and at the same time know yourself (you need only open your eyes that you're not helping anyone by it, and not saving anyone from anything! But tell me, finally," he uttered almost in a frenzy, "how such shame and baseness can be combined in you beside other opposite and holy feelings? It would be more just, a thousand times more just and reasonable, to jump headfirst into the water and end it at once!"“

Do you remember the woman who jumps into the canal in front of Raskolnikov earlier in the novel? The great metropolis claims its victims daily… And Sonya has through of it - but what makes her strong enough not to succumb to despair, this slender young woman with transparent fingers?

“He read everything in that one glance of hers. So she really had already thought of it herself. Perhaps many times, in despair…”

How can this frail woman transcend the horror of her “dishonorable and shameful position”?

“What, he wondered, what could so far have kept her from deciding to end it all at once? And only here did he understand fully what these poor little orphaned children meant to her, and this pitiful, half-crazed Katerina Ivanovna, with her consumption, and her beating her head against the wall.”

Raskolnikov needs Sonya - and he needs to understand how she preserved her soul filled with love and forgiveness and understanding - outside of the sin of the flesh:

““But it would seem that this very accident, this smattering of education, and the whole of her preceding life, should have killed her at once, with her first step onto that loathsome path. What sustained her? Surely not depravity? All this shame obviously touched her only mechanically; no true depravity, not even a drop of it, had yet penetrated her heart—he could see that; she stood before him in reality...

"Three ways are open to her," he thought, "to throw herself into the canal, to go to the madhouse, or ... or, finally, to throw herself into a depravity that stupefies reason and petrifies the heart." This last thought was the most loathsome of all to him; but he was already a skeptic; he was young, abstract, and consequently cruel; and therefore he could not but believe that the last outcome-that is, depravity-was the most likely.””

Sonya’s faith is her rock and salvation - but how does she preserve it in the filth and hopelessness of her life?

“"No, what has so far kept her from the canal is the thought of sin, and of them, those ones... And if she hasn't lost her mind so far... But who says she hasn't lost her mind? Is she in her right mind? Is it possible to talk as she does? Is it possible for someone in her right mind to reason as she does? Is it possible to sit like that over perdition, right over the stinking hole that's already dragging her in, and wave her hands and stop her ears when she's being told of the danger? What does she expect, a miracle? No doubt. And isn't this all a sign of madness?"

He stubbornly stayed at this thought.””

And here comes Dostoevsky’s great dramatization of the mystery of life-sustaining faith - the faith he discovered in the filthy barracks of hard labor life in Siberia:

“"So you pray very much to God, Sonya?" he asked her.

Sonya was silent; he stood beside her, waiting for an answer.

"And what would I be without God?" she whispered quickly, energetically, glancing at him fleetingly with suddenly flashing eyes, and she pressed his hand firmly with her own.

"So that's it!" he thought.

"And what does God do for you in return?" he asked, testing her further.

Sonya was silent for a long time, as if she were unable to answer.

Her frail chest was all heaving with agitation...

"Be still! Don't ask! You're not worthy!..." she cried suddenly, looking at him sternly and wrathfully.””

The leather-bound Gospel from which the two great sinners read of the resurrection of the human soul is the very one Dostoevsky received from the Decembrist wives (whose husbands were sent to Siberia after the unsuccessful anti-government coup that took place in December of 1825 - exiled by Nicholas I, the same tsar who exiled Dostoevsky in 1849) on his way to Omsk, the only book he could have on his bunk for four years, the book he preserved and cherished all his life - the one that was on his nightstand when he died in 1881…

““It was the New Testament, in Russian translation. The book was old, used, bound in leather.

"Where did this come from?" he called to her across the room.

She was still standing in the same place, three steps from the table.

"It was brought to me," she answered, as if reluctantly, and without glancing at him.

"Who brought it?"

"Lizaveta. I asked her to."

"Lizaveta! How strange!" he thought. Everything about Sonya was becoming more strange and wondrous for him.”

It was Lizaveta’s gospel… The other meek and timid holy fool…

"You've never read it?" she asked, glancing at him frowningly across the table. Her voice was becoming more and more severe.””

Fragile Sonya’s voice will strengthen in the course of the reading, will become prophetic, fortified by her faith in the resurrection of her innocent murdered friend…

“"Yes... She was a just woman... She came... rarely ... she couldn't. She and I used to read and ... talk. She will see God." How strange these bookish words sounded to him; and here was another new thing: some sort of mysterious get-togethers with Lizaveta-two holy fools.””

What brings about the resurrection of Lazarus - after the recriminations of Martha and Mary? Their faith in the POSSIBILITY of the resurrection - which is a miraculous and mysterious faith, the faith at the root of Russian Christianity…

““Then said Martha unto Jesus, Lord, if thou hadst been here, my brother had not died. But I know, that even now, whatsoever thou wilt ask of God, God will give it thee.'"

"Then when Mary was come where Jesus was, and saw him, she fell down at his feet, saying unto him, Lord, if thou hadst been here, my brother had not died.””

Is there hope for the redemption of Raskolnikov? We inadvertently cheered him on every step of the way towards the macabre success of his murderous undertaking - and we served as the accusatory chorus of his nightmares - sternly looking onto his transgressions against his own humanity though the open door… Now Dostoevsky asks us to commit to the impossible - to the unfolding of the miracle of redemption that Raskolnikov is about to undergo… Will he succeed? Do we believe in this POSSIBILITY?!?!?!

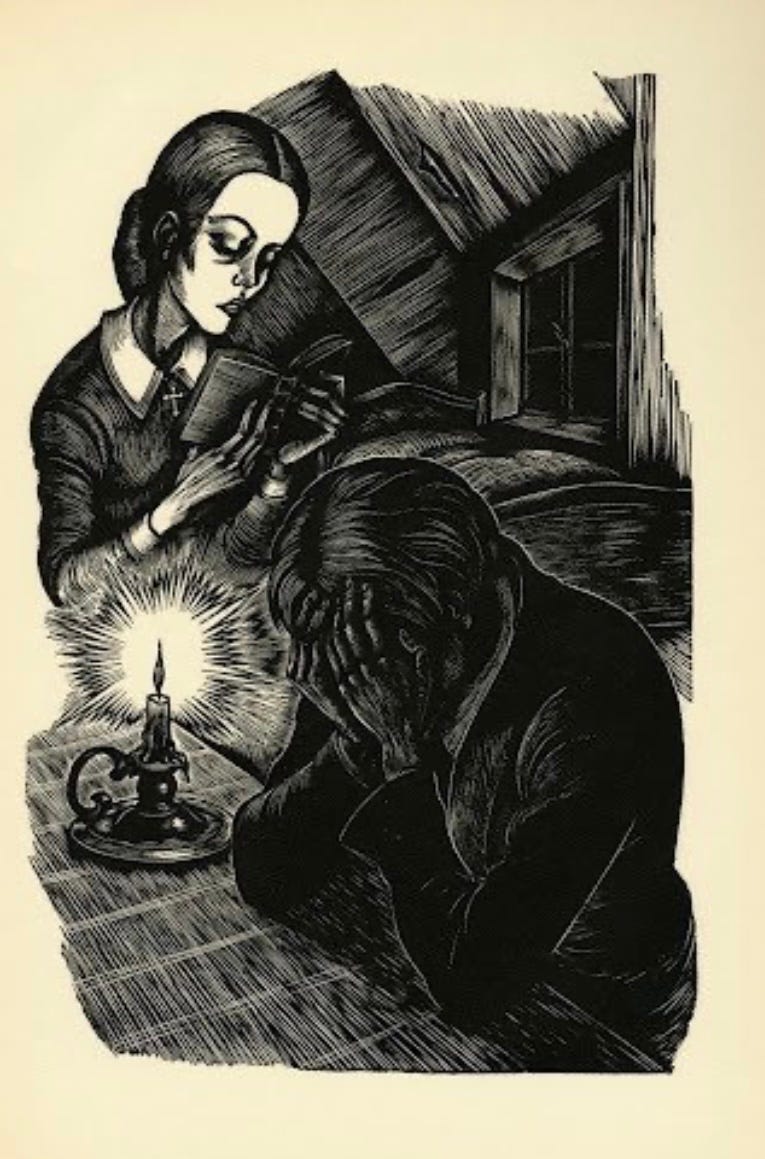

"That's all about the raising of Lazarus," she whispered abruptly and sternly, and stood motionless, turned away, not daring and as if ashamed to raise her eyes to him. Her feverish trembling continued. The candle-end had long been burning out in the bent candlestick, casting a dim light in this destitute room upon the murderer and the harlot strangely come together over the reading of the eternal book.”

Raskolnikov needs Sonya because she too laid hands on herself - and yet has strength to live - AND preserve faith…

““She went on looking at him, understanding nothing. She understood only that he was terribly, infinitely unhappy.

"None of them will understand anything, if you start talking with them," he continued, "but I understand. I need you, and so I've come to you."

"I don't understand." Sonya whispered.

"You'll understand later. Haven't you done the same thing?

You, too, have stepped over... were able to step over. You laid hands on yourself, you destroyed a life... your own (it's all the same!). You might have lived by the spirit and reason, but you'll end up on the Haymarket... But you can't endure it, and if you remain alone, you'll lose your mind, like me. You're nearly crazy already; so we must go together, on the same path! Let's go!"

"Why? Why do you say that?" Sonya said, strangely and rebelliously stirred by his words.

"Why? Because it's impossible to remain like this-that's why…””

Do you recall Liza - who understood what only a woman who loves deeply can understand - that the Underground Man was unhappy? That Lisa is Sonya now… Raskolnikov used all the rational arguments against her that the Underground Man used against Lisa - that she needs to change her life or else she will die of diseases alone and abandoned by the world… What Sonya and Liza understood was that the men delivering these tirades are themselves lonely and miserable and abandoned by the world, drowning in their own hubris and standing on the precipice of despair and self annihilation…

““She went on looking at him, understanding nothing. She understood only that he was terribly, infinitely unhappy.

"None of them will understand anything, if you start talking with them," he continued, "but I understand. I need you, and so I've come to you."

"I don't understand." Sonya whispered.

"You'll understand later. Haven't you done the same thing?

You, too, have stepped over... were able to step over. You laid hands on yourself, you destroyed a life... your own (it's all the same!). You might have lived by the spirit and reason, but you'll end up on the Haymarket... But you can't endure it, and if you remain alone, you'll lose your mind, like me. You're nearly crazy already; so we must go together, on the same path! Let's go!"

"Why? Why do you say that?" Sonya said, strangely and rebelliously stirred by his words.

"Why? Because it's impossible to remain like this-that's why…””

And in the big metropolis - someone is ALWAYS listening… This scene was SPECTACULARLY portrayed in the ballet - a wall separating two barren spaces - a solitary man gleefully absorbing information he hopes to use for his own benefit - and two solitary emaciated souls reaching out towards each other over a book that leads to the cross…

“And meanwhile, all that time, Mr. Svidrigailov had been standing by the door in the empty room and stealthily listening. When Raskolnikov left, he stood for a while, thought, then went on tiptoe into his room, adjacent to the empty room, took a chair, and inaudibly brought it close to the door leading to Sonya's room. He had found the conversation amusing and bemusing, and he had liked it very, very much-so much that he even brought a chair, in order not to be subjected again in the future, tomorrow, for instance, to the unpleasantness of standing on his feet for a whole hour, but to settle himself more comfortably and thus treat himself to a pleasure that was full in all respects.”

“The candle-end had long been burning out in the bent candlestick, casting a dim light in this destitute room upon the murderer and the harlot strangely come together over the reading of the eternal book.”

Fritz Eichenberg (1901-1990), German-American artist who illustrated all the final novels of Dostoevsky - the Great Five - which we are reading in the next four years…